Overzealous union-busting

Federal employee labor law is not exactly my jam. Perhaps I know enough to be dangerous. Nevertheless, it only took a small amount of time to see the clear error and overreach present in President Trump’s recent executive order that basically cancels collective bargaining across a huge swath of the government. Like with many Trump Administration efforts, there are things it can do, things it could possibly do, and things that make my head want to explode.

Under the law cited by the executive order, agencies or agency subdivisions do not need to negotiate with employee unions “if the President determines that—

(A) the agency or subdivision has as a primary function intelligence, counterintelligence, investigative, or national security work, and

(B) the provisions of this chapter cannot be applied to that agency or subdivision in a manner consistent with national security requirements and considerations.

(Emphasis added).

The administration is grossly misinterpreting the term “primary function.” The principal function of the Environmental Protection Agency, General Services Administration, and Federal Communications Commission is not intelligence, counterintelligence, investigative, or national security work. I’d guess that 99% of the secret Signal exchanges among employees at these agencies have nothing to do with them.

The White House’s “fact sheet” justifies the exclusions with tenuous connections to national security:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: “COVID-19 and the recent bird flu have demonstrated how foreign pandemics affect national security.” [Alas, COVID-19 exists again!]

International Trade Administration, Department of Commerce: “President Trump has demonstrated how trade policy is a national security tool.”

Environmental Protection Agency: “energy insecurity threatens national security.”

Veterans Affairs: “VA serves as the backstop healthcare provider for wounded troops in wartime” and “VA is also a backstop healthcare provider during national emergencies, and served this role during COVID-19.”

National Science Foundation: “NSF-funded research supports military and cybersecurity breakthroughs.”

Treasury Department: “The Treasury Department collects the taxes that fund the government and ensures the stable operations of the financial system.”

General Services Administration: “GSA provides cybersecurity related services to agencies and ensures they do not use compromised telecommunications products.”

A notable exclusion from the executive order’s coverage is Customs and Border Protection workers represented by the National Border Patrol Council (NBPC), which endorsed Donald Trump for President.

It’s hard to tell if there’s bad faith, high school-ish research, or EO-by-AI going on here. Maybe it’s all three. The executive order attempts to justify these conclusions by citing a 1980 FLRA case called Oak Ridge in support of the president’s conclusion that these agencies’ work directly relate to national security. I know nothing about whether Oak Ridge is still good law, but I can tell that Oak Ridge interpreted a different labor statute. The statute interpreted by Oak Ridge relates to which individuals cannot be in a bargaining units, not which entire agencies or subdivisions cannot have a bargaining unit.

Fired IGs Case Update - “The Process is important.”

On March 27, 2025, one battle in the Administration’s war on checks and balances within the executive branch was fought in the courtroom of District Court Judge Ana Reyes. Storch et al. v. Hegseth et al., 1:25-cv-00415, was brought by a number of Inspectors General to fight their removal by the President in January on the basis that their removal required 30-days notice and reasons to be provided to Congress. The oral argument in Storch went about as well as possible for the plaintiffs.

This case is about more than eight inspectors general who want their jobs back. It is really about the President’s ability under the Constitution to remove federal officials. Who can he fire for no reason at all? What sort of officials may be constitutionally protected from whimsical Presidential removal?

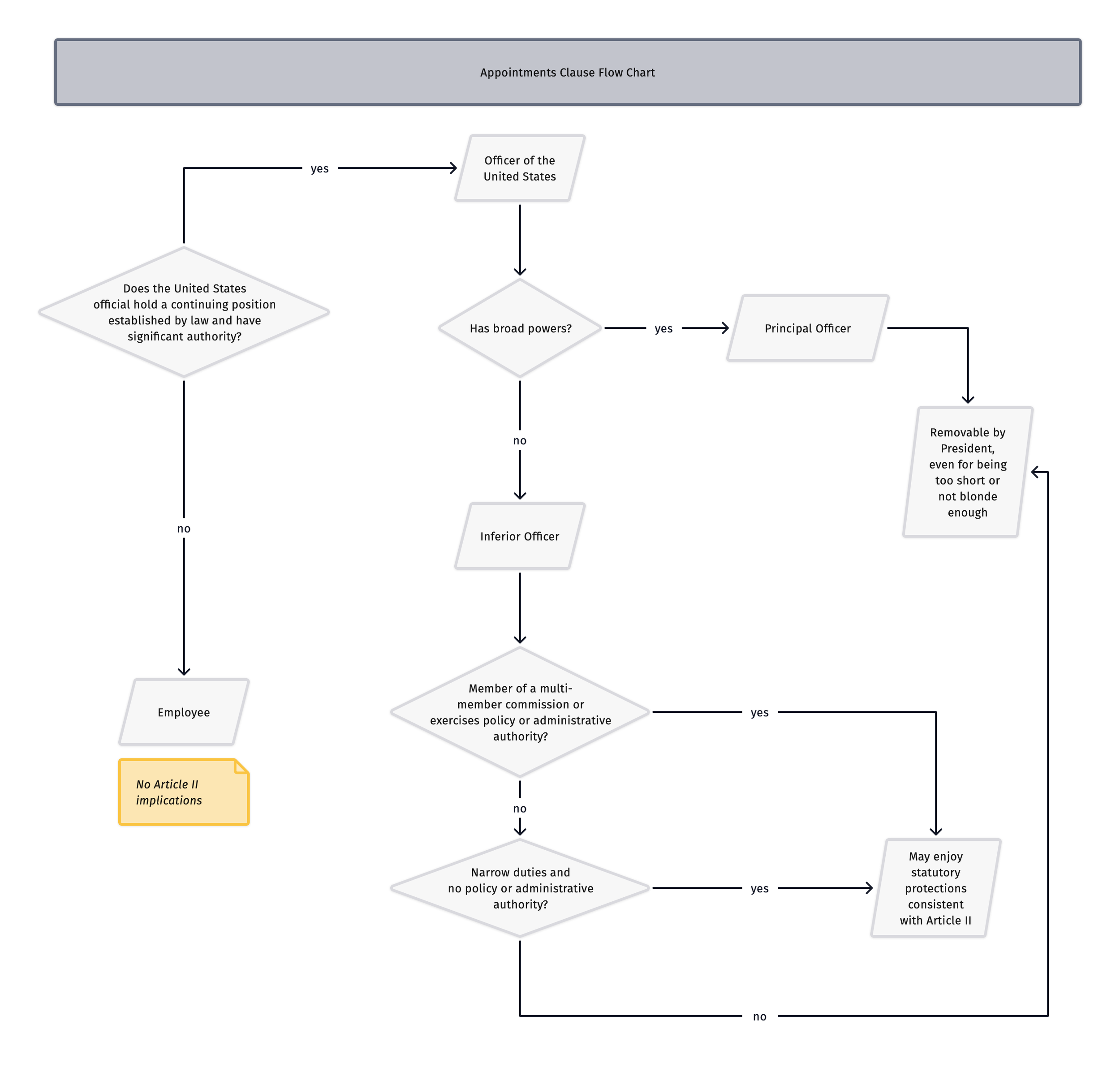

The parties have argued over whether the IG-plaintiffs are “principal officers,” “inferior officers,” or “employees.” Additionally, the parties have argued about the range of duties and authorities of IGs because if they are “inferior officers,” the Supreme Court has recognized that the President’s removal authority can have limitations under certain exceptions.

If the Appointments Clause tests make your head spin, here’s a flow chart that reflects the parties’ explanation of the current state of the law:

Judge Reyes indicated that she is likely to rule that inspectors general are “inferior officers” under the Constitution. She also indicated that she is leaning toward ruling that they have narrow duties and do not exercise policy or administrative authority. As a result, she would rule that the IG Act provision requiring notice to Congress provision is constitutional.

Judge Reyes also indicated that she would likely rule that statutory provision requiring advance notice with reasons to Congress is a statutory condition that must be met by the President. At one point, after counsel for the government argued that removal is not contingent on the notice to Congress, she asked him to “explain how it doesn’t say what it says.” She did not seem to find his argument to be persuasive as she laterstated that she is likely to find that the President did not follow the law. She stated that she was moved by the argument that the purpose of the advance notice to Congress is to give members of Congress an opportunity to intervene and try to persuade the President to not remove an IG. She admitted that she did not understand the importance of the notice provision until that was made clear in oral argument. “The process is important,” she stated from the bench.

Less clear is the appropriate remedy. The court took issue with counsel for the government’s contention that a ruling in favor of the plaintiffs would be a “pyrrhic” victory, since the President would likely simply remove the IGs again first they were reinstated. She pointedly countered that the IGs want a statement from the court that their removal was a “violation of law,” “decency,” and “not appropriate.” Nevertheless, she showed reluctance to order the IGs back into office just for the President to place them on administrative leave, give 30-day notice and reasons to Congress, and then fire them. On the other hand, the court expressed concern that without reinstatement, the message of the case would be the President is “breaking the law without consequences.” DOJ argued that returning them to office would cause “upheaval” within the offices of the inspector general, which have been operating under the plaintiff’s previous deputies. Back pay has be seen as an adequate remedy in other employment cases. The court likened the situation to ordering specific performance versus monetary damages in a contract case.

At the close of the argument, which went for about 2 hours, Judge Reyes thanked the attorneys for the preparation and argument skills; the law firm representing the plaintiffs pro bono; and the fired IGs, who, she said, likely made personal and financial sacrifices during their tenures as IGs. She thanked the fired IGs for “standing up” and contesting the “unacceptable” manner in which they were let go (i.e., a terse email). “That’s not how we do things,” she said.

Judge Reyes also indicated that a ruling was not expected soon, making a veiled reference to the pending complaint that the Justice Department filed against her in the DC Circuit Court of Appeals for alleged inappropriate statements from the bench in a case challenging the military’s transgender exclusion policy. This complaint may explain the judge’s comment at the opening of the hearing that she was “calm.” It appears that Judge Reyes wants the complaint to be resolved before issuing her ruling in another case involving the Administration.